Let us tell you the story of St John's Hospital

St John’s Hospital

The Jean-Lurçat museum and contemporary wall-hangings

St. John’s hospital in Angers is one of the oldest illustrations of French hospital architecture. The Great Hall for the Sick, a major edifice of gothic art in the west of France together with the chapel, the cloister and the grain loft form a remarkable example of mediaeval civil works.

A lay foundation

A foundation covered by royal patronage

The hospital equipment of the time was reduced to the strict minimum : two chaplaincies, two leper houses and a few monastic infirmaries which also cared for the lay. Around 1180, guided by Henry II Plantagenet (King of England) who had already set up similar institutions in Le Mans and several towns in Normandy, the Seneschal of Anjou, Etienne de Marçay, founded a large hospital dedicated to Saint John the Evangelist in the district of the Doutre which was growing rapidly. The closeness of the river Maine and one of its reaches, which flowed at the foot of the hospital, surely had something

to do with the choice of location, as it could be supplied by boat and the river could be used to transport the sewage away from the hospital.

The foundation was built for the poor and sick. In compliance with the legislation of the third Council of Latran, the hospital benefited from a chapel in 1184, served by 4 priests and later, around 1190 from a cemetery. Between 1203 and 1205, thirty monks, nuns and lay brothers, under the responsibility of a prior, observed the teachings of Saint Augustine, laying down its statutes, which were later confirmed by Pope Clement IV in 1267.

Thanks to generous donations from Henry II and a group of laymen and priests, the future of the foundation was secured. This was completed by the Treilles lock, some of the taxes from the Grand Pont Bridge, the free transport of salt, land, woods and town rents. Not all the sick were cared for. Those who had incurable diseases, the contagious, dangerous individuals and young children, were all left aside. The brothers had to speak to “Our Lords the poor” calmly, feed them well, care for them at night, make sure they weren’t cold and give them a decent burial. However, this notion of

service was less present at the end of the Middle Ages.

The hospital of the poor

From hospital to museum

From the 1480s, a serious internal conflict opposed the prior and his religious community with regard to the respect of the 13th century statutes. At the end of a series of legal cases which lasted more than 70 years, the Paris parliament gave over the administration of the building to 4 bourgeois elected by the aldermen, abandoned the monastic offices, and rewrote the statutes in 1554. The daily journal counts of the sick, preserved since 1536, show that there were, on average, 188 sick per day in 1656 and up to 671 in 1782. There were several patients per bed and their food seems less varied than that of the monks and nuns, who dined heartily on whale, sturgeon and oysters. The medicines were provided by the apothecaries in Angers until the hospital received an inheritance from Lucrèce Maumussard (indisécable) which allowed them to set up their own pharmacy which is still partly visible today.

In 1639 the Daughters of Charity, accompanied by Louise de Marillac, took over the running of the hospital. They received a visit from their founder, St. Vincent de Paul, in 1647. A report dated 1645 states that the hospital counted among its personnel, 10 monks, 8 Daughters of Charity, a doctor, an apothecary, a surgeon 46 servants and 20 washerwomen. In 1797 all the hospitals came under the common governance of the municipality. It was only in 1865 that all the sick were transferred to a new hospital, which is the present University Hospital. In spite of different road projects, the grounds of the old hospital were finally preserved from demolition. The Great Hall for the Sick was restored around 1900, by the architect Louis Magne and became an archaeological museum.

In 1968, the museum collections gave way to the wall hangings of the “Chant du Monde” (Song of the World) by Jean Lurçat. The Jean Lurçat museum of contemporary wall hangings was set up in 1986 in the old bathrooms and rooms of the hospital nuns which had become a municipal orphanage in the 19th century. Creative textile workshops were set up in the old maternity ward. The hospital buildings were all restored from 1988 onwards.

A new style: Gothic Plantagenet

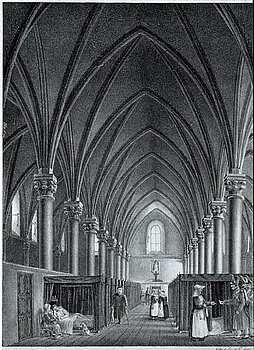

The Great Hall for the Sick

Today, you enter this vast hall from the opposite direction to that of the Middle Ages. The main entrance was located in the present rue Gay-Lussac, and access was via the cloister before being admitted to the Great Hall. The contrast is striking between the austere exterior made of schist and the white harmony of the interior. This vast hall of 60 metres by 22.50m was mentioned in 1188, but its strongly vaulted ceiling was probably not built until the beginning of the 13th century. Three naves of equal size separated by two rows of columns made for a remarkable unity of volume in this sober decoration (espace): the scrolled claws of its bases, capitals with simple plant motifs. Formerly, the hall was partitioned. There was one low wall which divided the central nave into two dormitories. In the 17th century, wooden partition walls cemented between the columns, separated the 110 men’s beds from the 112 women’s beds. Since 1962 the pharmacy has been present in the entrance to the hall.

In this showcase, you have the “Chant du Monde” by Jean Lurçat, a vast wall hanging which comprises 10 tapestries woven between 1959 and 1965 in the Aubusson workshops (Tabard, Goubely, Picaud). When Lurçat discovered the Apocalypse tapestries in Angers in 1937, he understood that tapestry can have a specific message. After the Second World War he invented the technique of counted shades, reduced colour ranges and numbered models. As a leader of the movement for the rebirth of French tapestry, he devoted all his energy to promoting this art form. The “Chant du Monde” is his personal message of peace and hope, the “Apocalypse” of modern times. The richness of vocabulary used by Jean Lurçat makes it one of the artist’s major works.

A well preserved hospital

The Chapel

Today, entrance is through the old choir and no longer via the 16th century Romanesque door with its historiated wooden panels whose base has just been uncovered. The chapel was built after the Great Hall for the Sick. It was consecrated in 1195 by Bishop Raoul de Beaumont and was built for the religious community and the sick who received their sacraments before being admitted. Two naves of the same height on a square layout are separated by two slendercolumns. The vaulting bears traces of a number of clumsy mistakes bearing witness to its enlargement. You can see the fine décor of the arcatures of the openings around the original door. The interior layout was modified in the 18th century. The main altar and the two lateral altars were installed in the north and surrounded by a communion table. Opposite the altars there is a loft with wooden panelling representing Saint Charles Borromée and the plague of Milan.

The cloisters and other community spaces

The Great Hall for the Sick was surrounded by two cloisters. The Grand Cloister was built thanks to a gracious donation of 8 000 pounds from René Hiret in 1623 and of which only one gallery remains today, running along the length of the present entrance. It was also called the cloister of the keepers in the 15th century and was enclosed in 1188 by the kitchen and housing quarters.

The foundations of a hexagonal washbasin were unearthed in 1874 and are still visible. It was the only water source. The Small Cloister has only three galleries in its present form. Two of these are of Roman inspiration with their semi-circular arches resting on twin columns. It is one of the rare cloisters of this period in our region. The sloping roof only dates from the 15th century. The Renaissance south wing with its charterhouse above was built by the famous architect Jean Delespine after 1534. It lies just next to the staircase of the old 15th century prior’s quarters which no longer exist today.

The question remains as to whether the fourth side was ever built or not. In the 17th century, latrines were built here. Under the courtyard there is still a vast arched cesspool dating from around 1540. The sewage was evacuated into the River Maine via a large collector which ran the length of the Great Hall for the Sick. The cloister did not function in the same way as that of the monasteries. It was a covered entrance, used as a sort of admissions hall. A number of buildings are missing today, so that it is difficult to understand the movement and internal workings of the people who lived and worked here. The same can be said of the monks’ quarters, the kitchens and the refectory. To the north there are still some 18th century buildings such as the washroom dating from 1752, which was transformed into a gymnasium. Other places which depended on the hospital were outside the enclosure such as the cemetery for the poor which was located at the present ‘place de la Paix’ from 1190 to 1776.

Well stocked grain lofts

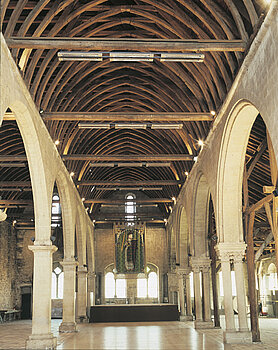

The grain lofts, cellar and school

The imposing building which opens onto the place du Terre-Saint-Laurent was built after 1188. At this time the Abbess of Ronceray mentioned the “rock of the chaplaincy” which referred to the cellar. This vast construction had two floors. The cellars which had two groined vault naves, separated by enormous square pillars, opened onto the enclosure thanks to the sloping ground. On the top floor the grain lofts themselves were divided into three naves separated by large semi-circular arches supported by twin columns dating from the 12th century, or simple pillars dating from the 16th century. The facades on the square and the ‘rue des Greniers-Saint-Jean’ made entirely of schist, formed the extremity of the hospital enclosure with long loopholes as the only openings. The primitive entrance is located on the limestone/tufa east side, with a series of twin bays running along the north gable.

The fine decoration and the number of bays in the grain loft are surprising for a simple supply store. Was it used as a hospice? There was frequently a separation between the infirmary and the hospice in the Middle Ages. 15th century records do tell us that grain was stored here.

The roofing was not visible as it is today. There was a floor used for extra storage space.

The lofts were linked to a mill. This ruin was replaced in 1824 by a school of charity, built by the architect Louis François. It is the present service building. Wine from the hospital vineyards was stored in the cellar. A spring running down the bare walls ran into two pipes and was used to flush the sewage down into the Maine.

In 1561, there was a project to make the lofts into a protestant place of worship, but this never came about. The great plague epidemics forced the lofts to be used to house the sick, especially in 1598. When Prosper Mérimée visited Angers in 1836, the building was still used to store grain and continued to be used for this purpose until the new hospital was opened in 1865.

Classified as historic monuments in 1862, the buildings were acquired by the town in 1868; however, the hospice commission had in the meantime rented them to a brewer. The cellars were used by the brewer until their transformation into a wine museum in 1932.

Since 1954, the lofts have been used for some prestigious shows, performances and receptions; among others the welcoming of Colonel Glenn the first American astronaut (1966), the inaugural concert of the New Philharmonic Orchestra of the Loire Region (21st September 1971) and the 10th anniversary of the twinning of Angers, Haarlem and Osnabruck (1974). The cellars are host to the Knights of the Anjou Sacavin wine tasting brotherhood, the oldest wine tasting brotherhood of its kind in France and provide an ideal setting for the enthronement of its new knights. Restoration carried out between 1992 and 1994 once again brings to life the remarkable architecture of the cellars while ensuring the indispensable improvement to facilities geared to receiving the general public. The south gable which gives onto the ‘square Tertre-Saint-Laurent’ was extended by several metres to include technical facilities.

An exceptional textile art collection

The museum of contemporary wall-hangings

Restored in 1986 to house the Jean-Lurçat museum of contemporary wall-hangings, this building presents permanent collections donated by Simone Lurçat (1988) and Thomas Gleb (1990). The Lurçat foundation completes the works with paintings, drawings, ceramics, lithographs and the Chant du Monde wall-hangings exhibited in St. John’s Hospital. The wall-hangings bear witness to the career of this artist (1892-1966), who lived through two world wars and whose painted works remain largely unknown to the general public. The works follow the cubist and then surrealist movements with Jean-Lurçat’s use of a vivid palette of colours making his work so attractive.

Thomas Gleb (1912-1991) was a little younger and a painter of Polish origin. His meeting with the tapestry weaver Pierre Daquin, at the beginning of the 60’s, propelled him into the New Tapestry movement. His “white on white” tapestries with a metaphysical dimension were among the “avant-garde” works of his time.

The museum also has a policy of temporary exhibitions dedicated to all the great names of French post-war tapestry (Lagrange, Prassinos, Wogensky, Matégot, Tourlière etc.) as well as to the artists of the New Tapestry movement of the 60’s and 70’s (Gleb, Grau-Garriga, Buic, Daquin, Olga de Amaral etc.) and the tapestry artists of the last few decades (Giannesini, Simard-Laflamme etc.) Other exhibitions display the diversity of textile expression such as the works of the Egyptian Wissa Wassef, the plaited works of Guy Houdouin, the knitting and lace works of Marie-Rose Lortet or the international triennial of mini-textiles.

François Comte,

Archaeologist, Angers city.

Sylvain Bertoldi,

Curator in chief , Angers Archives

Françoise de Loisy,

Curator of Cultural Heritage, Angers museums.

Translated by Jonathan Lloyd,

Head of English, ESSCA

2010