Let us tell you the story of Barrault - from mansion to museum of the fine arts

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

A constantly rebuilt, sumptuous mansion house

The Mansion of a well-known Financier

The Barrault mansion was restored at the same time as the fine arts museum and provided the opportunity to entirely rediscover this fine edifice which is as extraordinary from an architectural point of view as the Jacques-Coeur private mansion in Bourges. It was built between 1486 and 1493 for Olivier Barrault, Viscount of Mortain, one of the king’s favoured servants, treasurer of the Brittany region and three times mayor of Angers. He married Perrine Briçonnet who came from a wealthy family of powerful financiers from Tours who were very close to the king’s court.

The house had a very prosperous though short history because even if this “lovely, honest and sumptuous edifice whose decoration was the reflection of the beautiful town in which it was located” saw the visit of such honourable hosts as César Borgia, during Olivier Barrault’s time, or Marie de Medicis in 1619, we know by the notary acts of the period that from the middle of the 16th century it was no longer one whole building. It was purchased by the Great Seminary in 1673, rented to the bishop during work to the Episcopal Palace around 1695, and was the object of profound alterations at the beginning of the 17th and 18th centuries. During the revolution, the building was handed over to the department of the Maine et Loire which used it to house its central school and then, later on, in 1801, a museum. In 1805 the public library ccupied the premises and then both the museum and the public library became municipal buildings, the public library remaining here until 1977. Extensive renovation work was carried out on the roofs and interiors of the Barrault mansion between 1850 and 1854. This renovation work based on the museo-graphic work of the period led to the creation of long second storey galleries lit by the noonday sun.

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

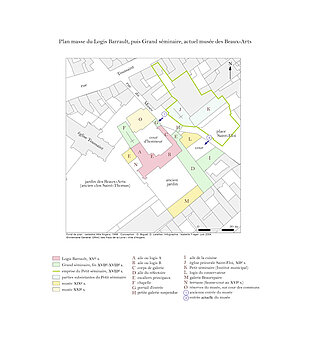

The archaeology of an urban pleasure

After acquiring a vast tract of land from the religious order at the Saint Aubin Abbey and then, using the site foundations of two pre-existing houses, Olivier Barrault built one of the first mansion houses between courtyard and garden according to new principles for the period which then became unchangeable up to the revolution. It was made up of two main buildings linked by a staircase and a gallery isolating the courtyard from the street. The building had a façade of 40m around the enclosed garden, of which, unfortunately, we know relatively little (the present esplanade). However, thanks to restoration work and ancient texts and plans, the first of which pre-dated the alterations to the seminary, an important intellectual restitution of the mansion is at last possible today.

The reconstitution of the facades and more especially the top parts of the building which were destroyed when the height of the seminary was raised, give an idea of the initial beauty of the edifice.

Today, some remarkable witnesses to this past glory still exist; the staircase, the sophisticated ribbed vaults of the entrance gallery (the courtyard of honour), the superb room on the ground floor and numerous en suite small private rooms.

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

, Ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

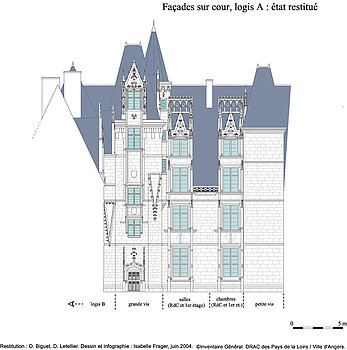

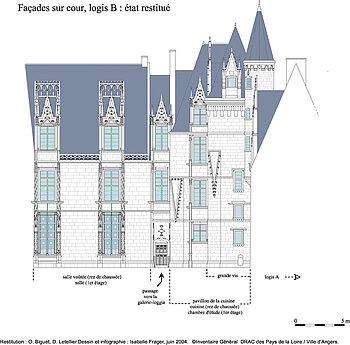

The facades of the courtyard of honour

presented a well-defined, picturesque silhouette, a mirror image of the princely dwellings of the Middle Ages. The height of the dormer windows is magnificent and they were structurally recreated according to the period thanks to precious archaeological remains. These dormer windows were unique in France apart from those of the now destroyed neighbouring chateau of the Verger in Seiches. However, they are preserved in some ancient engravings.

The quality of the construction work can be gauged by the schist masonry which was entirely faced both inside and outside with tufa stone whose large blocks (sometimes up to 0.80 metres long) gave rise to the name ‘barraude’ used in ancient texts to designate this size of stone. In the courtyard of honour the sheer verticality was accompanied by a sculpted décor of great quality based on present vestiges. The high windows in the vaulted room, particularly, present a skilful design of double small columns. They are decorated with plant peelings topped with pinnacles branching out to spiral stems which continued their upward climb to the top openings.

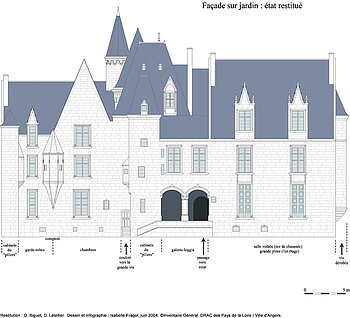

The garden façade…

inasmuch as we can imagine it in the 15th century, requires an even greater effort of imagination on the part of the spectator. This façade suffered from the alterations made to the seminary. Its restitution is largely based on a 1493 court case relative to urban regulations of adjoining houses between Olivier de Barrault and Pierre de Laval, the abbot of Saint Aubin. The unearthing of the remnants of a charming gallery on the ground floor with its two rows of ribbed vaults leading to the garden (restored during renovation work with the exception of the steps for safety reasons) constituted for the east façade, an important discovery for the history of civil architecture at the end of the 15th century. The interest shown in the garden by the local notables, (emulating King René in Angers castle), is evident from the use of this small room which is more than a simple loggia*, as, for the first time it establishes a direct, monumental link between the courtyard and the garden, a prelude to the grand classical compositions of the following centuries.

The original inner layout has also been almost totally reconstructed, with the precise position of the reception rooms, utility rooms and apartments. One of these on the first floor which is particularly spacious and gives onto both the garden and the courtyard, probably had a chapel at the end of the gallery running the length of the street. This succession of rooms was probably used by the master of the house when it was not being used for the pleasure of the short stays of princely dignitaries.

New space for a new museum

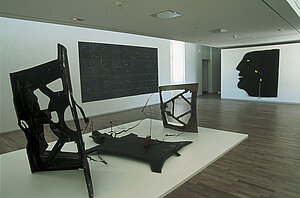

From 1999 to 2004 Renovation and extension work were undertaken in the museum of fine arts from 1999 onwards. The work enabled paintings, sculptures, drawings and art works to be exhibited in a surface area covering 3 000 square metres. The architects, Antoine Stinco responsible for the extensions and the new museo-graphic layout and Gabor Mester de Parajd in charge of the restoration of the sections covered by Classified Monuments, managed to reconcile heritage and modernity. The reception area for the public; auditorium, video room, and the information and relaxation section stretch over 1 000 square metres. They are accessible from the ‘place Saint-Eloi’ or the ‘Boulevard du roi René,’ the museum entrance was built on the site of the old seminary refectory which housed the David d’Angers art gallery from 1839 to 1984. The large patio under which there is a vast, modular, temporary exhibition room, gives a fine view of the public gardens of the museum of fine arts, the municipal library and David d’Angers Art Gallery the latter two being housed in the old Toussaint Abbey.

Remarkable collections presented to the general public

Museo-graphic Project

The architectural and museo-graphic project gives space to both the preservation of art works and reception of the general public. Acquisitions, as well as art collections from both private and state donations, enable a permanent exhibition based around two themes; the history of Angers and fine arts. Divided up across three floors they give visitors a chronological perspective. Programming of temporary exhibitions, (a 550 square metre floor area and graphic arts room) as well as the auditorium, alternate between national heritage and contemporary art.

Cultural activities are also organized in order for the general public to be familiar with the works of art.

Loggia :

word of Italian origin. Hall, gallery or porch open to the air on one or more sides. It is often a roofed, arcaded open gallery on an upper storey overlooking a court, though it can also be a separate arcaded or colonnaded structure.

Dominique Letellier,

Researcher, Regional Service of Inventory, Drac des Pays de la Loire

Olivier Biguet,

Curator of Cultural Heritage, City of Angers

Patrick Le Nouëne,

Curator and Director of Angers Museums

Anne-Pascal Seynhaeve,

Head of the Cultural Service for the public

Translated by: Jonathan Lloyd, Head of English, ESSCA

2010